The flexible self and the inflexible individual

What follows was originally published in 1981 and was called “Meet the Enemy.” See the posts Something I wrote a long time ago and More thoughts from the past.

What follows was originally published in 1981 and was called “Meet the Enemy.” See the posts Something I wrote a long time ago and More thoughts from the past.

Identity and self-opinion are acquired through a series of personal relationships. Our impressionable natures come under the influence of others and we respond by adopting new ideas and opinions or by resisting pressures to be more industrious or prompt or truthful. The situations created by personal interactions create facets of our personality that weren’t there before. Gradually we pick and choose which traits to keep and which to reject, sedimenting and consolidating this unpolished gem into an identity we can call our own.

Our need to maintain a belief in the underlying constancy of our identity often blinds us to the process by which we actively and willingly change ourselves. It’s not flexibility itself that we deny as much as those wholesale binges we go on when we incorporate someone else’s viewpoint. We recognize plagiarized traits more readily in others than in ourselves, as when a friend with a new mentor displays novel opinions, vocabulary, and mannerisms that he wears like new clothes before they’ve become his.

If I could just have more confidence about how I feel about a subject. I’ll hold on strongly to what I believe, and then someone comes along and I want to understand him and duplicate him so much that suddenly I let his viewpoint really affect me. It’s the damnedest thing, because I don’t like myself when I do that.

This from John Travolta, briefly a role model himself. It’s not always easy looking back on an impressionable self that was unaware of its now obvious imitative behavior, even if we later abandon those influences or see them as beneficial. To acknowledge this process in ourselves would mean admitting the possibility that we had no true identity of our own. We prefer to maintain the illusion that who we are comes from within, not without. This makes self-insight and change a more difficult project.

There is no innate, true identity, no one way to be that is correct, permanent, or guaranteed to be satisfying. The self is an idea that responds to social situations, expectations, and suggestions. But if this really is the nature of identity, why do I “feel like myself again” when I return from an ordeal or recover from a hangover? Why do I have the impression that there is definitely something about me that remains the same over time?

The Pressure of Existence

A group of people who share the same language and way of life operate with the same influences on their behavior: the length of the day, the use of indoor plumbing, the use of “he” to mean both “she” and “he,” the meaning of mañana. Realistic fiction abides by these constraints on reality; science fiction suspends them. When we anticipate the future we assume such conditions are in operation, that the rules apply. In a daydream we’re free to take liberties. The action in a daydream is not interrupted by such mundane necessities as hunger, thirst, and the need to find a bathroom. The constraints of reality are so basic that, unless they’re deliberately raised as theoretical questions, they never become an issue. They are not readily subject to doubt.

The belief that we are identical to ourselves over time captures this fundamental feature of reality, a feature we have imposed on the world to make it intelligible. It is not an innate identity that makes an individual feel continuously the same. Rather, it is the commonly repeated experiences of a shared world that make us identical to ourselves over time, as well as to each other.

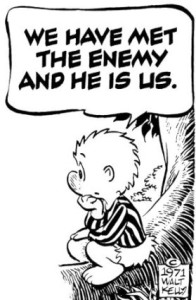

Society exerts substantial pressure on us to conceive of ourselves as continuous and limited. We must be responsible for our intentions and past actions. We must confine ourselves within a range of acceptable roles: there are only a limited number of life plans available. We live by a system of rewards and punishments for accepting and rejecting inherited institutions. The punishment for pushing the limits of society’s ideals is isolation — to be labeled abnormal, deviant, a weirdo. It is to be denied a respected place in the social complex we have been taught to need. Reward is merely the other side of the card. Society is not a distinct, separate referee calling the shots in this game. There is no conspiracy of perpetrators against their victims. The personification of society as the enemy is only a personification, that is, an illusion. We are they.

Even though our natural flexibility survives the constraints of reality and the pressures to conform, we are not encouraged to regard it as a useful tool, and it can grow out of our control with disuse. The general conception of flexibility is that of insincerity — to be only acting, to be playing the part of someone you’re not, to be “plastic,” artificial, hypocritical, at worst a liar. In this way we learn that flexibility is undesirable, and, conditioned as we are to crave social acceptance, the value of flexibility and its potentially liberating nature will fail to be realized, or else realized at considerable cost. We expect to find continuity, and in the process of looking for it we create our own inertia.

The idea of an unchanging identity is built into daily reality, into its typical, routine, recurrent events. We become habituated not only to our material environment and a set of people but also to ourselves, to the roles repeatedly required of us. We then carry with us, to all situations, a set of familiar and automatic assumptions about ourselves. Making life routine is a necessary adaptation to the complexity and variety of possible experiences, but in this process we sacrifice some of our inherent plasticity, and limit the potential and promise of ourselves and the opportunities we encounter.

The Ascent of Man

Because the complexity of modern civilization makes a high degree of self-consciousness likely, it is inevitable that we become more aware of possibility, indeterminacy, and the lack of any absolutes. As a historically aware civilization, we know there are many different directions in which we can develop, and we know the ease with which a random event — recognized or unnoticed at the time — can determine that direction. The modern mind must make choices and realize the responsibility that possibility and choice entail. At the same time, we have acquired greater insight into the nature of the socially constructed world — its history and dynamics showing us that we are on our own when it comes to giving meaning to the human life within it. We can no longer have confidence in an interpretation merely because it has historical precedents or is shared by many people. Everyone learns that “everybody’s doing it” is classic faulty reasoning.

The inflexibility of the individual mirrors the problem of change for society as a whole. Social, economic, and political systems, originally designed for a particular set of circumstances, no longer function when these conditions no longer hold. When habitual patterns of thought prove inappropriate or too rigid for the demands of novel situations — when certainty recedes — anxiety increases, and we feel even more of a need to believe in ourselves as permanent and inflexible. If we can believe in our own unity and continuity, we can impose stability on the world. To deny that we create our own image and are responsible for its maintenance can keep anxiety down, but this leaves us unprepared for the thoughts and events that will strike when they can no longer be suppressed.

Anxiety monitors the problematic regions of the human psyche and the human environment. The mind is actively evolving only in those areas that are capable of making us anxious, the areas where we are still learning. To suppress anxiety is to stifle further evolution. Anxiety should force us to become more aware of the taken for granted background of experience. It presents an opportunity to understand ourselves. Unexamined assumptions lead us to expect that the future will be a direct continuation of the past. Anxiety reveals those assumptions as questionable and exposes the areas of life where we have been unwilling to change, and where we are now, consequently, vulnerable.

The majority of our thoughts and actions throughout a typical day are nonreflective: We carry out routines, caught up in the stream of experience. When we reflect on ourselves we become aware of the stream itself, as if bringing our heads above water. Insight occurs only in reflection, and reflection arises only when we encounter an obstacle that forces us out of our usual underwater attitude. Anxiety situations are automatically reflective. They compel us to examine the past and future in an attempt to analyze our situation and its possible consequences. By taking this process under control, by pushing it deeper into the assumptions that form the background of thought, we can become more self-conscious.

We increase self-consciousness when we identify a pattern that was previously unrecognized, for instance the connection between eating chocolate and breaking out in hives, or between sexual intercourse and pregnancy. This is useful information that can be programmed into new recipes and techniques. Likewise, it is possible to recognize patterns of behavior that follow from incorrect assumptions: that someone we judged unfriendly is in fact painfully shy, or that our lack of artistic or athletic ability is a misconception left over from childhood experiences. To increase self-consciousness is to convert unrecognized determinants into matters of choice. Anxiety is a signal that should engage reflection and positive action. To use it to increase understanding is truly “self-help,” as opposed to a self-administered psychoanesthetic that attempts to do away with the anxiety itself.

The human creative process — the creation of social and personal reality — is intimately associated with anxiety. There should be something positive in the recognition of our active role in the continuous creation of the world. By formulating the process — by identifying and thinking about our powers — we give ourselves the option of intervening and exercising choice, of participating in a consciously chosen identity and future. What is characteristic of our species is the ability to change the way we think when new circumstances require that we learn to see things in new ways. This reorientation of perspective is a process that ideally continues throughout the lifetime of an individual and throughout the evolution of our species. In fact this is the evolution of our species.

Related posts:

Something I wrote a long time ago

More thoughts from the past

Image source: Jim & Nancy Forest

References:

The John Travolta quotation is from Timothy White, “True Grit Tenderfoot” Rolling Stone, No. 321 (July 10, 1980), p. 34

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.